Groundbreaking, PetroChina-CNPC refinery for PDVSA heavy oil. It is to be China’s largest. (April 2012)

Over the past few weeks, I have been looking at the state of the Venezuelan-Chinese oil alliance that Hugo Chavez has so fervently championed. The picture that emerges is not what one might expect. Here is an overview, in qualitative terms. [Correction: I originally wrote Ramirez reported that PDVSA produced “60,000” new barrels of Faja oil in 2013. He actually said “20,000”.]

A. Structural Changes – Vertical Integration with China

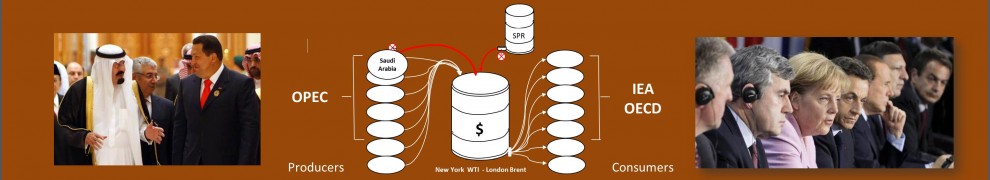

Till now, commentators have looked primarily at the obligations of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (BRV) to send oil to China to repay Beijing’s huge loans. However, there are major changes afoot in the structure of this relationship, no matter who succeeds Hugo Chavez. Developments on the ground in both countries show an energy infrastructure buildup will soon bring significant cross-border vertical integration. Soon, Venezuelan oil will not be shipped to China simply to fulfill financial-and-contractual obligations, but also for locked-in infrastructural reasons.

All indications are that the Chinese side is actively fulfilling the obligations it entered into ca. five years ago (esp. December 2007) to build oil tankers, pipelines and refineries in China in order to import and process Venezuelan heavy crude.

Billions are being invested and tens-of-thousands of Chinese workers are being employed. Indeed, maximizing domestic Chinese jobs has always been a strong preoccupation of Beijing in this relationship. (INTERFAX’s Shanghai bureau recently quoted me about this: ”Interfax, China Energy Weekly,” Oct 27–Nov 2, 2012, pp. 6-7.)

B. PDVSA’s new-production obligations

So too, since the failure of the 2002-03 strike by the previous leadership of PDVSA, commentators have closely followed production statistics for the new, Bolivarian PDVSA. The interest was to discern how PDVSA’s chronically depressed production would affect shipments to the U.S., the oil market and PDVSA’s ability to finance Chavez’ heavy public spending. However, the question is becoming, “Can PDVSA increase production in sync with new Chinese capacity downstream?” While the U.S. will remain an important PDVSA market, its new obligations to China will increasingly define both its export revenues and China’s willingness to extend credit to the BRV.

A growing energy interdependence of China and Venezuela (specifics in future posts) indicates Beijing will no longer be “merely” concerned about getting enough oil to pay back its loans. Now, Beijing has to worry about the prospect of sitting on multi-billion dollar white elephants in the form of under-used downstream capacity inside China, and lots of laid off Chinese workers. This is what will happen if PDVSA can’t soon realize constant and significant increases in Faja production. (Note, last year PDVSA’s Ramirez reported that only 60,000 [12Mar13 correction: he said “20,000” – T.O’D.] new Faja barrels had came online.)

C. Can PDVSA increase upstream Faja production in sync with the Chinese downstream capacity build?

So, will Mr. Ramirez (or whomever Mr. N. Maduro appoints as the new PDVSA president if-and-when Maduro replaces President Chavez) be able to meet PDVSA’s oil obligations to China? The answer is not simple; but it looks to me to be: yes, probably (that is, absent any prolonged presidential-succession or other political crisis).

Till now, the way PDVSA has ramped up oil shipments to China has been largely to “rob Peter” (i.e., decrease shipments to the U.S. market) “to pay Paul.” (i.e., to ship it to China). The thing is, given the increased amounts PDVSA must ship China two-to-three years from now, merely redirecting shipments is not a sustainable option. To continue meeting its growing obligations to China, PDVSA must fairly soon begin to register a significant, absolute increase in Faja production. This must be making Beijing a bit nervous.

In this regard, it is interesting to note that PDVSA has been seriously strapped for cash for over a year, even before the 2012 election spending. However, repeated requests by Bolivarian leaders for more loans from Beijing have reportedly been rebuffed. At the end of last November, Messers Ramirez and Giordani went to Beijing asking for cash; but they got none even after ceding Beijing lucrative gold-mine and oil-field contracts. (Bloomberg’s Bogotá bureau quoted me on this, 25 Jan 2013.) And, just a couple weeks ago, Mr. Jaua was reported to have also unsuccessfuly sought loans in Beijing. (Juan Nagel at Caracas Chronicles saw this failure linked to the subsequent Bolivar devaluation).

In any case, Beijing needs PDVSA to increase production. My research indicates there is a possibility that PDVSA is getting close to overcoming some oil-production bottlenecks in the Faja. As I’ve discussed previously, these bottlenecks are mainly due to a lack of infrastructure in remote Faja locations, including both oil-sector and civil infrastructure.

E. Summary

In sum, no matter who succeeds President Chavez, the future of any significant new Venezuelan production is tied to Asian markets–not only China, but also India, Japan and South Korea. The U.S. market, as I’ve shown in previous blogs, simply will not provide sufficient demand to absorb a serious expansion of Faja supply.

For this, and other geostrategic reasons flowing from Chinese great-power aspirations, China will not abandon Venezuela; but they are not about to play the role of what in Venezuela is known as the “pendejo” (pejorative for the fool, sucker, dumbass, …). They are not particularly interested in the political orientation of their Venezuelan partners, either now or down the line. And, since about early 2010, they started demanding a certain modicum of fiscal discipline, accountability and transparency on the part of the BRV in spending their money.

The Chinese did not come to Venezuela for reasons of “solidarity”, much less “social-economic development.” They came for oil. President Chavez, of course, did everything he could to elicit ancillary benefits, and China was willing to oblige, up to a point. Now, the time to consummate the oil union is near. Beijing needs new oil to flow. Its enthusiasm for an endless courtship, with profligate spending of their money, has worn thin.

In future blogs, I’ll martial data and references relevant to this evolving story.

Very intersting article, one other story about this topic : http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China_Business/OB07Cb01.html

LikeLike

Powerful article, the sort of info one would pay for. Keep on.

LikeLike

Isn’t the output from the Canadian oil sands heavy oil like Venezuelan crude? Can/is the Canadian oil replace the Venezuelan crude in US refineries? What about the North Dakota oil — is that heavy crude also?

LikeLike