President Santos of Colombia recently went to Caracas where he and President Chavez signed a letter of commitment for the “Binational Project on the Venezuela-Colombia Oil Pipeline” to run 3,000 km. from Venezuela’s Faja heavy-oil region, west across Colombia to the Pacific port of Tumaco. (El Universal and El Universal). After many disappointments in recent years in collaborations with PDVSA, Latin American presidents haven’t endorsed many joint projects lately. Nevertheless, Santos was beside himself with enthusiasm after the five-hour meeting on 28 November, declaring “Wherever we’ve mentioned this, people’s eyes open wide.” (Reuters)

Chavez signed a letter of commitment for the “Binational Project on the Venezuela-Colombia Oil Pipeline” to run 3,000 km. from Venezuela’s Faja heavy-oil region, west across Colombia to the Pacific port of Tumaco. (El Universal and El Universal). After many disappointments in recent years in collaborations with PDVSA, Latin American presidents haven’t endorsed many joint projects lately. Nevertheless, Santos was beside himself with enthusiasm after the five-hour meeting on 28 November, declaring “Wherever we’ve mentioned this, people’s eyes open wide.” (Reuters)

Let’s look at some data to see if Santos and Chavez are really onto somehing here.

THE PACIFIC-CONNECTION TREND

This is the latest of several similar porjects, including the soon-to-come-online widening of the Panama Canal, the Brazilian road through Bolivia that sparked indigenous protests against Evo Morales (Stratfor, 28 Oct 2011), and a Chinese plan for a rail line to ship coal across Colombia that Santos also endorsed in February 2011 (Financial Times, 13 Feb 2011). These all have one thing in common: opening up shorter routes for commodity exports from Latin America’s Atlantic and Caribbean coasts to the Pacific Ocean, then on to Asia and especially China.

But, how important is a new pipeline across Colombia? That depends on a couple factors:

- Frst, whether the new oil boom coming online in Latin America will continue to find a robust market in North America as well as a Chinese market?

- Second, just how expensive and slow is it to ship ol from LatAm’s Atlantic and Caribbean coasts to China?

- (Well, it also depends on whether PDVSA will be producing enough Faja oil anytime soon, or, perhaps there might be other regional users? I’ll return to this later.)

First, let’s look at the trajectory of US import demand, and, second, the geo-economics of sending supertankers back and forth from LatAm’s Caribbean and Atlantic coasts to China.

US SUPPLY AND DEMAND TRENDS: WANING IMPORT DEMAND?

An interesting article in Petroleum Intelligence World (PIW) (“Latin America Picks Bad Time for Oil Boom” Nov. 14, 2011 http://www.energyintel.com/Pages/About_PIW.aspx) pointed to significant US and Canadian non-conventional production growth from, respectively, tight-oil fracking and tar sands, while US thirst for oil has leveled out for some time now, especially as the US government conservation push continues (albeit tepid), along with mandates for increasing production of corn ethanol and other alternatives. The most recent US Energy Information Agency (EIA) Short-Term Energy Outlook of 6 Dec 2011 said:

“Domestic crude oil production [i.e., U.S. -T.O’D.]increased by 110 thousand bbl/d in 2010 to 5.5 million bbl/d. Projected production increases by roughly 200 thousand bbl/d in 2011 and by a similar amount in 2012. This rising trend in production is driven by increased oil-directed drilling activity, particularly in on-shore shale formations. The number of on-shore oil-directed drilling rigs reported by Baker Hughes increased from 768 at the beginning of 2011 to 1,113 on December 2, 2011.”

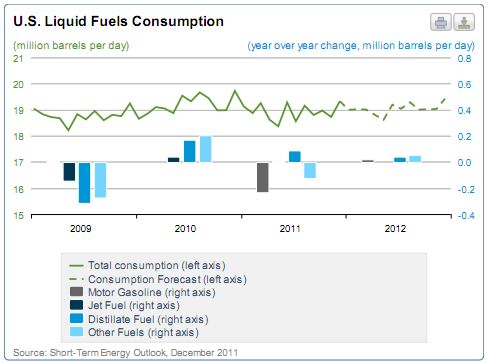

And, at the same time as production grows, oil-and-liquids imports have generally declined:

“The share of total U.S. consumption met by liquid fuel net imports (including both crude oil and refined products), which has been falling since 2005, is expected to be 45 percent in 2011 and 46 percent in 2012. The 220 thousand bbl/d drawdown in commercial and government stocks in 2011, which contributed to lower imports, is reversed in 2012 with stocks rising by an average 40 thousand bbl/d.”

So, indeed, a general trend of oil’s share of imports declining all the way back to 2005, albeit with an upward tick predicted for 2012. (We’ll see in a moment that U.S. consmption of oil-and-liquids has been down throughtout these years as well.) It si notable that this decrease has been quite robust wether prices rose of fell: In 2005 prices were taking off, then they crashed in 2008 and then rose again a year or so later. Furthermore, the liquids decline includes refined products (which should be of particular concern to Venezuela as it has always sent a good deal to the U.S.). In fact, it is striking that the December EIA report says refined product imports are actually at their lowest since 1945.

Compare two EIA graphs (again Dec 2011) treating the two contributors to this general trend. First, US crude oil and liquid fuels production. Notice how domestic production has been increasing. And I dont’ believe anyone thinks there will be less domestic oil from fracking coming online over the next decade (Anecdotally: I recently drove through north-central Pennsylvania and south-central New York State and motels across the regions were full of drilling crews up from central Penna., with nightly rates inflated accordingly). So too, there won’t likely be any drop in US Gulf of Mexico oil coming online in that time.

been increasing. And I dont’ believe anyone thinks there will be less domestic oil from fracking coming online over the next decade (Anecdotally: I recently drove through north-central Pennsylvania and south-central New York State and motels across the regions were full of drilling crews up from central Penna., with nightly rates inflated accordingly). So too, there won’t likely be any drop in US Gulf of Mexico oil coming online in that time.

At the same time, consider that the EIA data shows U.S. liquid fuels consumption, shown next, at roughly 19 mbd for the entire time shown. In years past, this had been up around 21 mbd.

So, while Latin America has many new oil projects coming online, U.S. import demand is waning. This means LatAm access to Asian markets will acquire increasing importance (perhaps delayed by a global return to recession in 2012 and a general drop in oil prices, but, that’s another matter).

THE TRANSPORT PROBLEM FOR LATIN AMERICA’S OIL BOOM

In principle (that is, to first-order) the world oil market is just one “Global Barrel” (as this blog is titled!). And, new recessions aside, clearly world demand is projected to continue rising over the long term. So, all the oil coming online in Latin America can just be shipped to China, India and etc., no? Yes, of course it can. However, look at a map, and you’ll quickly see why the profitability of this is significantly less than selling to the U.S. or, for that matter, Europe.

With almost all the new oil on the Atlantic side of the continent, and supertankers still unable to transit the Panama Canal, it is a really long haul to reach China. But, what if Santos’ and Chavez’ pipeline gets built?

I’m no expert on sea-transit times. So, I’ve resorted to the “Sea Distance Calculator” at http://sea-distances.com/ and the results are a bit of a surprise.

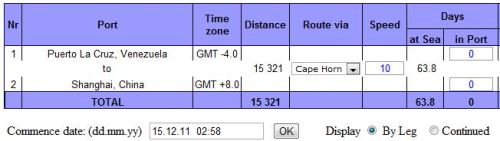

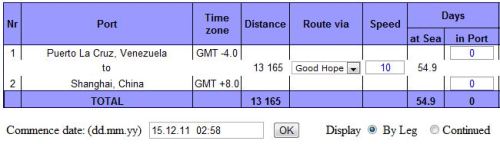

The first two graphics below show the distances for two different possible routes for oil exported from the Faja via Venezuela’s Puerto La Cruz on the Caribbean coast to China:

- First, down south in the Atlantic, through Cape Horn and west across the Pacific to Shanghai, China

- Second, down south and east across the Atlantic through the Cape of Good Hope below Africa and then up across the Indian Ocean, into the Pacific to Shanghai.

I was a surprised at the results (well, I had a suspicion or I would not have tried both possibilities). The result in the calculator are:

- 63.8 days at sea via Cape Horn, and

- 54.9 days at sea via the Cape of Good Hope.

So, I’ll assume the Cape of Good Hope is the actual route. (Everyone I’ve talked to in Venezuela and the US always seemed to assume that tankers go to China via the Cape of Good Hope.)

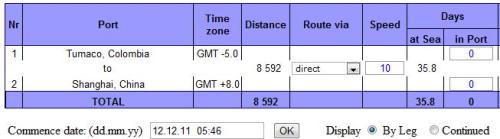

But, what if oil got to the Pacific Coast of Colombia, using the Santos-Chavez pipeline to the port of Tumaco just north of the Ecuadorian border? The calculator gives just 35.8 days at sea.

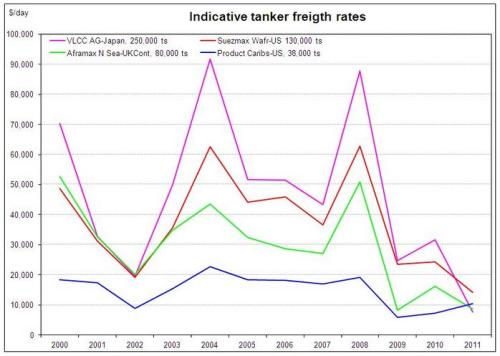

So, the difference is about 55-36 = 19 fewer days at sea. Now, look at the cost of shipping for supertankers on the following graph:

Note, the price per day of transport in large (here, VLCC) tankers has fallen considerably since 2008. However, over the past decade the price has ranged between $10,000 to $90,000 per day. Further, one must remember that the tankers have to go both ways—ida y vuelta–returning empty to pick up another load of oil. So, let’s look at the number of round trips a given tanker could make from Venezuela to China with and without this pipeline.

ECONOMICS WITH AND WITHOUT THE SANTOS-CHÁVEZ PIPELINE

Assuming zero time lost in ports (the time in ports is constant across both cases anyway, no matter which route a tanker takes), then, without the pipeline we have:

365/(55 x 2) = 3.3 trips/year.

While, with the pipeline we have

365/(36 x 2) = 5.1 trips/year.

So, for the same investment in building a tanker, this gives a percentage improvement in utilization for the capital investment with v. without the pipeline of:

(5.1/3.3) x 100 = 150%

Not bad. Of course, in this comparison, the cost of transport via the proposed Venezuelan-Faja to Colombian-Pacific-Coast pipeline is not zero; although pipelines cost less per unit distance than tanker transport.

Nevertheless, not only does the pipeline save considerably on capital investment in tankers, and the cost of transport per trip, the other way to look at this is that there is potentially a bottleneck in how much oil can be delivered to China due to how many round trips per any tanker can make. Consider the following:

“’Supertanker’ is an informal term used to describe the largest tankers. Today it is applied to very-large crude carriers (VLCC and ULCCs) with capacity over 250,000 DWT. These ships can transport 2,000,000 barrels (320,000 m3) of oil/318 000 metric tons.[46] By way of comparison, the combined oil consumption of Spain and the United Kingdom in 2005 was about 3.4 million barrels (540,000 m3) of oil a day [47]” (Ref: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_tanker)

Okay, using this information, say our fleet of CNPC-PDVSA and SINOPEC-PDVSA tankers carry 2.o million bbl of oil/trip. That means, with this pipeline, each could transport to China:

5.1 trips/tanker x (2.0 x 10^6) bbls/trip/year, that is: 10,200,000 bbls of oil per tanker annually

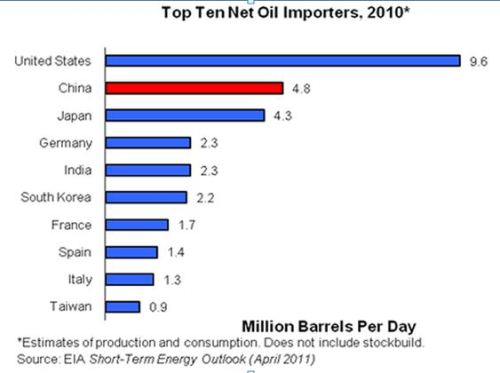

How important is that to China? the EIA country report on China from April 2011 giving the consumption of oil by China as 4.8 x 10^5/day (see chart below, and(http://www.eia.gov/countries/cab.cfm?fips=CH)

So, at (4.8 x 10^6) bbls/day in Chinese imports, this means each tanker could supply about 2.1 days of Chinese imports per year.

REFLECTION:

The veneer of ideological motivation which President Chavez has constantly given to oil trade with China in a “special relationship” while, right to the north and close by is the till-now seemingly insatiable US market, has done much to undermine the credibility of any actual market logic for China-centric oil projects (Please remember, I’m not saying that the US won’t continue to be an important customer, that’s not the point, just that it likely cannot absorb the new LatAm oil boom).

Today’s Bolivarian PDVSA is still struggling at home to reverse a decade of declining oil production, and has left the rest of Latin America littered with abandoned or stalled energy projects President Chavez promised PDVSA would carry out. The laudable cause of “Latin American energy integration” and of improved energy supplies and infrastructure generally has been left to suffer in Ecuador, Bolivia, Brazil, Argentina, Trinidad & Tobago and etc. with little to show for a decade of their collaborations with PDVSA. However, this pipeline, and any similar projects that would facilitate oil shipments to Chinese and Asian markets have their own, rather sound material-economic logic.

Santos’ statement of this pipeline’s importance is not hype; but the likelihood of its completion anytime soon, and of there being sufficient oil produced in the Faja to fill the pipeline any time soon will remain very low until PDVSA’s managerial and technical capabilities are significantly improved and/or it is joined by a major ally with the appropriate technology, capital and managerial capabilities.

In this regard, one can easily imagine this proposed pipeline having a spur originating somewhere in the Gulf of Venezuela, north of Maracaibo, for tankers from Brazil’s pre-salt and the entire Caribbean region to come and pump their cargoes into the new pipeline, joining with future oil from the Faja. In fact, Petrobras would be ready for this pipeline well before PDVSA and the Faja are ready.

Another neat post with lots of conventional-wisdom debunking.

The punchline is right in the last paragraph, though: considering the woeful state of the infrastructure needed to support the Red Apertura (e.g., your previous post), what you’re engaged in here is an exquisitely sophisticated econometric approach to measuring our chickens before the eggs are even laid, much less hatched…

LikeLike

Thanks. Re the punchline: Indeed!

Re: future eggs being counted, yes. However, a reason to go into these things now, in some detail, is that I think there is insufficient discussion in opposition circles as to what will be the _future_ constrains on and trajectory of the Venez. oil sector. And, for the _present_, most of the opposition underestimates that some increased production can be accomplished now. If they believe they are going to be running the biggest oil sector in LatAm soon, I’d hope by now there would be more analysis and lively debate coming out, beyond focusing on critique of the present government. There is some, but I’d expect much more.

LikeLike

Pingback: With a USA-dependent oil sector, Chavez can’t help Ahmadinejad | The Global Barrel

Pingback: The Sell-out of “Socialism” « Undustrialism